I have been asked a number of very strange and abstract questions in the past 16 years of practice, but I do not think anyone has ever asked me “What is the most important muscle?” What do you think is the answer, the abdominals, the glutes, or the quads? All of those would be good answers but none of those muscles would qualify for the most important muscle in the body.

The answer is the diaphragm. It doesn’t matter if you’re a sprinter, a marathoner, football player, tennis player, swimmer, cyclist, or even a couch potato. The diaphragm is central (pun intended) to every athletic movement and the quality of that movement. Without the diaphragm all other movements would be uncoordinated, not to mention that we breathe with the diaphragm.

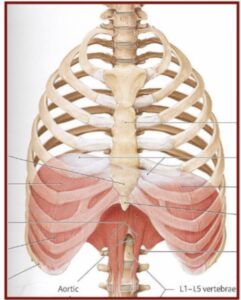

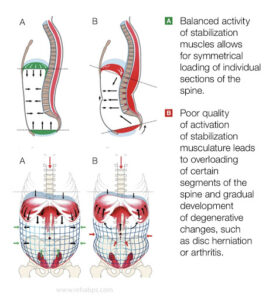

First, let’s discuss the action of the diaphragm. The human lungs work on a negative pressure system which essentially means that when we inhale we are forcing air in and when we exhale, we allow it to escape. So when we inhale, the diaphragm contracts and moves inferiorly causing a vacuum for the lungs and when we exhale, the diaphragm relaxes and rises to allow air out. During these same actions an incredible thing happens, as the diaphragm contracts and moves downward it builds pressure between itself and the pelvic floor, this is known as intra abdominal pressure or IAP, this IAP is the prime stabilizer of the spine! No, not the lumbar musculature, not the abs and not the mystical CORE that everyone is training into oblivion. Now, in order for the diaphragm and IAP to properly stabilize the spine and in effect the rest of the body, we must first remember how to breathe.

First, let’s discuss the action of the diaphragm. The human lungs work on a negative pressure system which essentially means that when we inhale we are forcing air in and when we exhale, we allow it to escape. So when we inhale, the diaphragm contracts and moves inferiorly causing a vacuum for the lungs and when we exhale, the diaphragm relaxes and rises to allow air out. During these same actions an incredible thing happens, as the diaphragm contracts and moves downward it builds pressure between itself and the pelvic floor, this is known as intra abdominal pressure or IAP, this IAP is the prime stabilizer of the spine! No, not the lumbar musculature, not the abs and not the mystical CORE that everyone is training into oblivion. Now, in order for the diaphragm and IAP to properly stabilize the spine and in effect the rest of the body, we must first remember how to breathe.

“Remember how to breathe?” This is a common patient response, and then they lose their minds when I tell them they can keep themselves out of back pain by learning how to breathe. Stick with me, if you have ever watched an infant breathing, you have probably noticed that their giant Buddha-like belly expands and falls with little to no movement of the ribs or chest. This is the exact opposite of how 90% of the adult population breathes. Instead most adults, due to extended amounts of seated posture and general lack of movement start to breathe using accessory breathing muscles in the neck and shoulders. These accessory muscles are only meant to be used for labored breathing, as in exercising. Switching to these back-up muscles as the main breathing apparatus leads to shoulder tension, lumbar spine pain, headaches and a whole host of other problems.

Now that we have discussed the general issues with the thoracic diaphragm, we will now move to why it is an athlete’s most crucial muscle. For the purpose of this article, I will use a distance runner, but this does not mean that the diaphragm is not equally important for non-endurance athletes. All runners have at some time probably heard that you should try to breathe in a 3:2 ratio, 3 steps breathing in, 2 steps breathing out. This is supposedly done to keep the runner from landing on the same foot with a full exhalation. This theory on breathing is absolutely right, but it needs more specification: 3:2 ratio of abdominal breathing. If you are not breathing abdominally, but rather using the chest and shoulder musculature, the efficiency of the breath becomes very low and your power output becomes decreased. That means you are running slower and you will fatigue faster.

As I stated before, when the diaphragm works properly, a tremendous amount of IAP is built which acts as a balloon, or better yet as a weight belt! This works to create stability of the lumbar spine better than any weight belt you could buy. When a runner breathes properly through the abdomen, the diaphragm links the upper body to the lower. This has an effect of stabilizing the spine allowing for more power production from the shoulders and hips. For swimmers, throwing athletes, racquet sport athletes, golfers, and even cyclists this stabilization of the spine is key for elite performance. The ability of the spine to provide a foundation for movement is why we core train an athlete in the first place. But we are now understanding that the most important tool for core stabilization is the diaphragm.

As I stated before, when the diaphragm works properly, a tremendous amount of IAP is built which acts as a balloon, or better yet as a weight belt! This works to create stability of the lumbar spine better than any weight belt you could buy. When a runner breathes properly through the abdomen, the diaphragm links the upper body to the lower. This has an effect of stabilizing the spine allowing for more power production from the shoulders and hips. For swimmers, throwing athletes, racquet sport athletes, golfers, and even cyclists this stabilization of the spine is key for elite performance. The ability of the spine to provide a foundation for movement is why we core train an athlete in the first place. But we are now understanding that the most important tool for core stabilization is the diaphragm.

Diaphragmatic breathing becomes the anatomical and functional link between the upper and lower halves of the body. One of my favorite books is called Anatomy Trains by Thomas Myers. This book explains that the body is now seen more like one giant muscle with multiple fascial pockets, rather than individual muscles encased in the fascia. For those of you who don’t know, fascia is the connective tissue that is infused through every structure of the body, it is much like the thin sinew you see in a nice marbled steak. The importance of paying attention to the fascia for training and treatment purposes grows as the body of research constantly mounts. These fascial pockets or slings connect all parts of the body, but some areas have stronger connections, such as the fascia around the low back, abdomen and the glutes. When we have the cortical ability to relax the abdomen while still breathing properly we allow for a tremendous power transfer from arm swing, to the core, to the glutes, and finally to the ground. This is how great athletes can produce so much more power than the majority of other people.

Diaphragmatic breathing becomes the anatomical and functional link between the upper and lower halves of the body. One of my favorite books is called Anatomy Trains by Thomas Myers. This book explains that the body is now seen more like one giant muscle with multiple fascial pockets, rather than individual muscles encased in the fascia. For those of you who don’t know, fascia is the connective tissue that is infused through every structure of the body, it is much like the thin sinew you see in a nice marbled steak. The importance of paying attention to the fascia for training and treatment purposes grows as the body of research constantly mounts. These fascial pockets or slings connect all parts of the body, but some areas have stronger connections, such as the fascia around the low back, abdomen and the glutes. When we have the cortical ability to relax the abdomen while still breathing properly we allow for a tremendous power transfer from arm swing, to the core, to the glutes, and finally to the ground. This is how great athletes can produce so much more power than the majority of other people.

Sure, good and sometimes great athletes, who have poor breathing habits can make it to the peak of their sport. Athletes are tremendous compensators, and they always find a way to excel. However, most of these athletes will do this as the expense of a joint, muscle, or region of the body. This is often where their greatest weakness is found and their most common injury. Even non-athletes will do the same thing and given enough repetition of an insulting movement, injury will soon occur. It is up to practitioners like myself and others in fields to educate, treat and train people to maximize their performance and decrease injuries.

Breathing Exercises

When trying to learn how to breathe you test what muscles you are using to breathe simply by sitting tall with your hands around your waist. Place the hands just above the pelvis with the thumb falling in the muscles of the flank and low back and the fingers falling into the soft tissues of the abdominal wall. With a normal breath, do you feel your hands expand or do you feel your chest move up and down? If you feel your hands expanding all the way around your lower abdomen and low back, you are breathing properly. If you feel your chest move, you are not breathing with your diaphragm.

To rehabilitate your breathing pattern begin by placing yourself on your knees, with your hips over your feet, and elbows on the floor (i.e. child’s pose). Keep your upper back flat and breathe deep into the lower pelvis feeling the lateral abdominal wall expand. Try breathing in for the count of 3 and out for the count of 5.

To rehabilitate your breathing pattern begin by placing yourself on your knees, with your hips over your feet, and elbows on the floor (i.e. child’s pose). Keep your upper back flat and breathe deep into the lower pelvis feeling the lateral abdominal wall expand. Try breathing in for the count of 3 and out for the count of 5.

The more advanced position is the 3 month supine position where you lay on your back with your hips and knees flexed to 90 degrees. Keep your chin in a tucked position while placing your hands over the lateral and anterior sides of the lower abdomen. Breathe in again for the count of 3 and out for the count of 5. If done correctly, you should feel the lower ribs expand as the diaphragm pushes pressure against the pelvic floor.

The more advanced position is the 3 month supine position where you lay on your back with your hips and knees flexed to 90 degrees. Keep your chin in a tucked position while placing your hands over the lateral and anterior sides of the lower abdomen. Breathe in again for the count of 3 and out for the count of 5. If done correctly, you should feel the lower ribs expand as the diaphragm pushes pressure against the pelvic floor.

We hope that you find these exercises helpful. You can find this video on our YouTube channel here. Feel free to email or call us with any questions. Remember, it’s our mission to help you become healthier than you have ever been.

Daryl C. Rich, D.C., C.S.C.S.